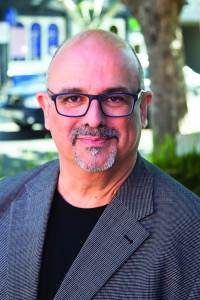

Clinical psychotherapist Frank Zoumboulis says ‘helicopter’ or ‘tow-truck’ parenting affects the emotional development and well-being of young people.

Helicopter parents take an overactive and excessive interest in their child’s life. All parents want the best for their child but they can become over-involved, smothering, overbearing, interfering and over-controlling. I also call them tow-truck parents because they wait for an accident to happen and then steam in and clear up the mess.

“They have clear opinions about who is the right teacher for their child, what sport they should play, they want their child to be in the popular group and they offer disproportionate assistance, rather than allowing their teenager space. These parents don’t enjoy uncertainty, so they over-prepare and supervise intensely and interfere with their child’s opportunity to do something for themselves and to deal with the natural consequences of their actions.

“In the 1940s and 1950s the approach to parenting was not to smother or spoil a child. John Bowlby was a contemporary British psychiatrist and child-development specialist who saw attachment as complementary to exploration. He said a child needed to feel secure enough and good enough about themselves to explore, but helicopter parents shut down exploration. They dampen a child’s confidence and interfere with their ability to develop resilience and to find their own feet. Kids end up ill-equipped to deal with basic day-to-day stuff, they can’t manage emotional responses and they are super-dependent on the parent. In my practice, I’ll see a 16-year-old with their parent and the parent completes the child’s sentences and answers their questions for them.

“Some parents don’t risk a child participating in something because they feel their child may fail, but children need to experience failure to thrive.”

“Helicopter parenting isn’t to be confused with parents who are present – young people need a present parent. That’s a parent who can manage their own anxiety so when their child challenges their authority or questions them, that parent doesn’t go into a meltdown. A present parent is one who listens to their child because when your child talks, it encourages them to develop independent thoughts and they begin to have some critical thinking skills. Give your child some time with a problem so they can try and solve it themselves while making it clear you are available and allow them to come to you when they need help.

“Some parents don’t risk a child participating in something because they feel their child may fail, but children need to experience failure to thrive. They need to sit with the burden of upset. Helicopter parenting alleviates that burden of suffering, but this interferes with a child’s ability to develop their own experience of struggle and success, or struggle and trauma and then recovery.

“When your child feels hurt or defeated, sit with them and let them feel it and then your child will move on. Parents think that when a child is hurt and they fail at something that it is the beginning of a downhill slide and that their child will keep going downhill – they don’t. A child sits with it for a while and then moves on to the next thing. Parents are more likely to be the ones who catastrophise, but that’s about their anxiety of being a good enough mother or father.

“Ask yourself ‘how much am I hovering?’. Ask someone who knows you and who is prepared to tell you the truth. Often parents don’t realise they’re stifling their child’s potential for greater development. So be more of an observer rather than a doer and remember that your child needs to master the ordinary to be extraordinary.”